CYP21A2 Gene Analysis in Southern Iranian CAH Patients and a Brief Review of the Mutation Spectrum

-

Zangene, Danial

-

Department of Medical Genetics, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

-

Moravvej, Ali

-

Neonatal Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

-

Ilkhanipoor, Homa

-

Department of Pediatric Endocrinology, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

-

Amirhakimi, Anis

-

Department of Pediatric Endocrinology, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

-

Afshar, Zhila

-

Department of Pediatric Endocrinology, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

-

Entezam, Mona

Department of Medical Genetics, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran, Tel: +98 71 32349610; Fax: +98 71 32349610; E-mail: entezam@sums.ac.ir

Entezam, Mona

Department of Medical Genetics, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran, Tel: +98 71 32349610; Fax: +98 71 32349610; E-mail: entezam@sums.ac.ir

Abstract: Background: CYP21A2 gene mutations are responsible for more than 95% of Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH) disorders with autosomal recessive inheritance. Most of these pathogenic mutations originate from the CYP21A1P, a neighboring pseudogene with 98% homology, due to unequal crossing over or gene conversion events. Mutation identification of the gene could be beneficial for accurate diagnosis and outcome prediction.

Methods: Twelve unrelated patients with CAH diagnosis were recruited for genetic counseling. To ensure distinct amplification of the CYP21A2 gene rather than its pseudogene, the complete sequence of the gene was amplified through two overlapping fragments by specific primers. The entire sequences were screened by direct Sanger sequencing using new sequencing primers.

Results: Only two pathogenic point mutations were identified. The c.293-13C>G, also known as In2G, and the c.955C>T mutations were found in 37.5 and 33.3% of alleles, respectively. One patient showed homozygous gene deletion. We also reviewed recent reports on CYP21A2 gene mutations in Iran.

Conclusion: Evaluating the ethnicity-specific gene mutation data is significant for populations with diverse ethnic groups including the Iranian population. Although several common mutations have been reported as causative mutations among CAH patients, identifying only two common point mutations in Fars province would help prioritize exon sequencing and reduce the cost and time of genotyping.

Introduction :

Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH; MIM: 201910) is a group of common autosomal recessive disorders that interrupts normal steroidogenesis in the cortex of the adrenal glands 1. These steroid hormones, including cortisol, aldosterone, and adrenal androgens, develop from cholesterol in multistep enzymatic pathways 2.

21-hydroxylase deficiency (21-OHD) caused by CYP21A2 gene mutations, is responsible for more than 95% of CAH cases and has distinct clinical classifications 3. The classic form is a life-threatening condition, with a prevalence of 1 in every 16,000 newborns worldwide 4. The prevalence of the nonclassic form is 1 case per 600 persons; although it is generally asymptomatic, it may cause infertility in females 5.

In many laboratories, evaluating 17-hydroxypro-gesterone (17-OHP) is the main approach to CAH diagnosis, and the accumulation of 17-OHP is interpreted as 21-OHD 6. Some studies suggest that replacing 17-OHP with 21-deoxycortisol as the CAH biomarker can reduce false-positive test results 7. However, based on the EMQN guideline, CYP21A2 genotyping is the best approach for 21-OHD testing and CAH diagnoses 8.

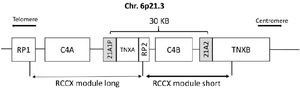

The CYP21A2 gene (MIM: 613815) which encodes the 21-hydroxylase enzyme and its pseudogene, CYP21A1P, are located approximately 30 kb apart in the high-gene-density HLA III region on chromosome 6p21.3 9. The gene and pseudogene along with their neighbor genes are located in a genetic unit called RCCX unit 10. There are usually two RCCX modules on each chromosome; One RCCX module includes RP1, C4A, CYP21A1P, and TNX A, and the other RCCX includes PR2, C4B, CYP21A2, and TNX B genes, (Figure 1) 11,12. Furthermore, the CYP21A2 gene and its pseudogene show 98% homology in their sequence 13. These situations accelerate gene conversions and unequal crossing-over events in this region, resulting in transferring mutations of pseudogene to active CYP21A2, and even partial or complete deletion of the gene and neighboring regions 5.

According to previous studies, a group of nine mutations is responsible for 21-OHD in the majority of CAH patients in the world; but the frequency of each mutation is different in every ethnicity 14,15. Thus, prioritizing mutations and related gene regions would make CYP21A2 genetic analysis more feasible and cheaper. Moreover, the CYP21A2 gene analysis is a valuable complement for predicting phenotype as well as confirming the diagnosis 16. Here, we evaluate the CYP21A2 variants in Iranian families from the south of the country. We also reviewed the prevalence and type of CYP21A2 mutations in different parts of the country based on previous studies.

Materials and Methods :

Patients and sampling: Twelve families were referred for genetic analysis by endocrinologists. CAH diagnosis was confirmed clinically according to medical examination and paraclinical findings. Patients were selected from various regions in the south of Iran. Peripheral blood samples were collected from all patients and their parents. DNA was extracted using Parstous Kit (ca.t number A101201) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and quantity of DNA were assessed by the NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ND-1000) as well as agarose gel electrophoresis. The research project has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Approval ID: IR. SUMS.REC.1400.378). Informed consent was obtained from all of the participants.

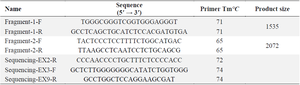

PCR amplification and the sanger sequencing: To ensure specific amplification of CYP21A2 gene rather than its pseudogene, the complete sequence of the gene was amplified through two overlapping fragments by specific primers. All coding sequences and exon-intron boundaries were screened by direct Sanger sequencing of fragments with an average size of 600 bp, using new sequencing primers. Table 1 shows the characteristics of primers.

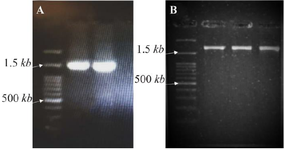

All fragments were amplified in a final reaction volume of 25 µl using PCR Master Mix (Ampliqon, A140303) and 0.6 mol/L of each primer, along with 30 ng of DNA. The MgCL2 final concentration was 1.5 mmol/L. The fragment-1 PCR cycling parameters were as follows: initial denaturation of 95°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 70°C for 30 s, 72°C for 60 s, and a final extension of 72°C for 5 min. The fragment-2 cycling parameters were as follows: initial denaturation of 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 64°C for 30 s, 72°C for 90 s, and a final extension of 72°C for 7 min. All PCR products were controlled by Agarose gel electrophoresis (Figure 2).

Sanger Sequencing was provided by the Codon Biotech Company, Tehran, Iran. Gene deletion analysis was performed as previously described 17 by the Pishgam Biotech Company, Tehran, Iran, (www.pishgambc.com).

Data analysis: All sequences were aligned to the CYP21A2 sequence (NM_000500.9) and CYP21A1P sequence (Transcript: ENST00000342991.10) to ensure the specific amplification of the CYP21A2 gene. The potential effect and pathogenicity of observed single nucleotide variants were then evaluated using online tools including SIFT, Provean 18, PolyPhen2 19, Mutation Taster and Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD), as well as Clinvar and HGMD.

Furthermore, we performed a PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science search to review the spectrum of reported CYP21A2 mutations in Iran, and extracted the frequencies of mutations from studies on 244 CAH-affected families.

Results :

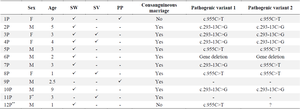

According to family history 10 (83%) of marriages were consanguineous, among them 70% were first-cousin. There was a positive history of CAH in only one pedigree. Patients comprised six girls and seven boys ranging from 1 to 10 years old from the south of the country. They had ambiguous genitalia (simple virilizing) at the delivery time or Salt-Wasting problems in the initial weeks or suffered from precocious puberty in childhood (Table 2).

Mutation analysis was performed for all individuals. Direct sequencing of the entire region of CYP21A2 gene by overlapping specific primers identified causative mutations in 17 out of 24 alleles. One patient (family 6P) showed whole gene deletion in a homozygous state. In one patient only a single mutation was identified, and in the two remaining families no mutation was detected. Figure 3 shows the chromatograms of identified mutations in each family. The c.293-13C>G -SNP code rs6467, also known as In2G- in the second intron was the most frequent photogenic variant with a frequency of 37.5%. After that, the c.955C>T -SNP code rs7755898, also known as Gln318*- in the 8th exon was the only pathogenic variant among the studied patients (Table 2). A total of 22 polymorphisms were also observed through the analysis.

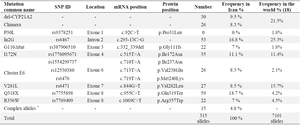

According to previous studies on 244 families with CAH disease in Iran, eight different DNA mutations as well as gene deletions and chimeras were responsible for CAH pathogenesis (Table 3). Most of the families were from Tehran; the capital city in the center of the country and consisted of different ethnicities.

Discussion :

Herein, we evaluated the entire CYP21A2 gene in 12 unrelated families from south of Iran and found two deleterious mutations, In2G and Q318X as the most frequent pathogenic mutations in the studied families. Each of these mutations has its specific mutagenesis mechanism and origin, as well as different distributions in any population. Although several common mutations have been reported as causative mutations among CAH patients, identifying only two common point mutations in Fars province is interesting. The patients were ethnically Persian and Lur. This could help prioritize exon sequencing and reduce the cost and time of genotyping.

Until 2022 several studies have performed genotyping approaches to investigate CYP21A2 alleles in Iranian CAH patients. According to previous studies reviewed in table 3, In2G and Q318X are the most reported mutations in Iranian families 20-27. Our findings coincide with previous studies. Besides, I172N and In2G are among the most prevalent mutations which cause the classic form of CAH worldwide, and V281L mutation is the most common mutation causing the nonclassic form 20,28,30.

The c.293-13A/C>G (In2G) mutation makes an adverse splicing site and disrupts the CYP21A2 pre-mRNA 31,32. In this case, the patient 21-OH enzyme will have only 0-1% residual function, and the classic form of CAH disease will emerge 33. Overall, the In2G allele is the world's most frequent pathogenic point mutation in the CYP21A2 gene. Studies on the origin of this mutation suggest that the In2G mutagenesis can spontaneously occur due to conversion events; so the frequency of this mutation is nearly the same in every population 34,35. We found In2G mutation in 9/24 studied CYP21A2 alleles (37%).

The c.955C>T (Q318X) nonsense substitution turns the glutamine codon (CAG) into a termination codon (TAG). This mutation leads to a completely nonfunctional 21-OH enzyme, and the patient manifests the classic symptoms of the CAH disease 36. HLA haplotyping and segregation studies reveal the old origin of this mutation. So, the frequency of this mutation can be very diverse in every population. Moreover, it is suggested as a founder mutation in some populations 35,37. Nevertheless, this pathogenic variant is rare in many countries. In the USA and middle Europe, the frequency of this mutation is only 2.6 and 3.7%, respectively among all CYP21A2 pathogenic variants 38. In Iran however, the Q318X is one of the main reasons for the CYP21A2 gene corruption and CAH disease. We found the Q318X mutation in 7/24 studied CYP21A2 alleles (29%).

Iran had a specific geographical location throughout history and comprises various ethnic groups, suggesting high genetic heterogeneity. However, founder mutations and other factors mainly consanguineous marriage result in homogeneity in some genetic loci and mutations 39,40. Albeit, more studies are needed to better clarify the mutation origin.

Conclusion :

Evaluating the ethnicity-specific gene mutation data is significant for populations with diverse ethnic groups including the Iranian population. Although the study is limited by the small number of patients, according to our findings we recommended to sequence exons 3 and 8 (In2G and Q318X mutations) as the first step for CYP21A2 genotyping.

Acknowledgement :

This manuscript was supported by a grant from Shiraz University of Medical Sciences under the Agreement No. 22941. The ethical code of the research project by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences was: IR. SUMS.REC.1400.378. We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Dr. Saman Nahid and Farzanegan Laboratory for doing biochemical tests and blood sampling as well as Pishgam Biothech company for confirming deleted alleles. We are also, very thankful to all the patients and their families for their kind collaboration.

Conflict of Interest :

The authors declare no conflict of interest for this article.

Figure 1. Bimodular form (RP1–C4A–CYP21P–XA–RP2–C4B–CYP21–TNXB) of the RCCX region of chromosome 6p21.3. Cyp-21A2 gene and its pseudogene are shown in the gray boxes.

|

Figure 2. Gel electrophoresis results. A) PCR products of the first fragment (exons 1-6). B) PCR products of the second fragment (exons 5-10).

|

Figure 3. Families' pedigrees and images of founding mutations.

|

Table 1. Primer sequences for amplification of CYP21A2 gene

|

Table 2. clinical features and genotyping results of studied patients

P= Proband, F= Female, M= Male, SW= Salt-Wasting, SV= Simple virilizing, PP= Precocious puberty.

* Identical female twins.

** Adrenal Crisis was diagnosed.

|

Table 3. characteristics of various mutations reported in previous studies

* Each complex allele has a couple of mutations. These alleles are: I172N+V281L, I172N+I2G, I2G+V281L, I2G+G110Δ8nt, I2G+Q318X, V281L+Q318X, G110Δ8nt+Q318X, Cluster E6+Q318X, and R356X+P453S.

|

|